How Incremental Efficiency Gain Translates into Global Impact

Small Numbers, System-Level Consequences

In aviation, incremental efficiency gains reshape fuel demand, emissions, commercial airline economics, and aircraft demand. A clear historical precedent is the introduction of winglets, which prevent vortex formation around the wingtips and reduce drag by 3-5%. Winglets are now standard on nearly all commercial aircraft and have been retrofitted to thousands of aircraft already in service. Aviation Partners Boeing, who manufacture and install winglets, project that “by year-end 2030, Blended Winglets and Split Scimitar Winglets will have saved in excess of 20 billion gallons of jet fuel thereby eliminating over 210 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions.”

Aviation Efficiency Gains Are Structurally Hard

Aviation efficiency gains are typically very difficult to achieve, owing to a litany of structural impediments:

Average aircraft lifespan of 20-30 years;

Aircraft order backlogs are at historic highs;

Certification - while crucial - limits rapid change;

Capital intensity of technological development

The above factors create an industry environment that systematically resists step-changes in technological development, meaning that aviation rarely sees the rate of change typical of Silicon Valley; for example large language models like ChatGPT, or the release of the iPhone 4 (incontrovertibly the last good iPhone upgrade).

In aviation, incremental shifts are the name of the game. General Electric’s GE9X jet engine, for example, delivers a 10% efficiency improvement over the previous generation GE90. Even single digit efficiency gains are significant; since its introduction, General Electric has achieved a 3.6% reduction in fuel burn since the GE90’s initial launch specification.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, the scale of the aviation industry and its fuel burn mean that the value of such improvements becomes massive across fleets of dozens of aircraft with tens of thousands of flight hours annually.

Defining the 4% Efficiency Gain

MicroTau’s sharkskin-derived Riblet Modification Package is capable of efficiency gains up to 4%. What this means in practice is that fuel burn savings can appear moderate on a per flight basis; roughly 750 kg (1,653 lb, 247 US gal) of fuel saved for a 767-300 flying Los Angeles to New York, or 215 kg (474 lb, 71 US gal) of fuel saved for an A320 flying Barcelona to Istanbul. Note that efficiency gains are not constant across the entire flight profile; the effect is greatest at cruise and the aerodynamic impact during takeoff and landing are taken into account here.

These savings numbers scale rapidly when aircraft utilisation is taken into account. The utilisation rate of A320s and 767-300s typically approaches 3,000 hours and 4,000 hours annually, netting 450,000 kg (992,000 lb, 148,000 US gal) and 160,000 kg (353,000 lb, 52,650 US gal) in fuel savings annually respectively for these routes.

Industry-Wide Gains Matter More Than Breakthroughs

In aviation, a primary driver of innovation impact is how widely and quickly a technology can be deployed. Winglets, which deliver 3-5% efficiency gains, are retrofittable, and have been incrementally certified since the first rollout in the 1980s, are now traversing the skies on tens of thousands aircraft and delivering billions of gallons of fuel savings. Conversely, moonshot alternatives such as radically new airframes and propulsion systems will require entirely new supportive infrastructure and extremely capital-intensive development, testing, and certification programs. These designs largely remain in the concept stage, yet to make their intended impact. Products that can have an immediate impact on the existing global fleet create a substantially greater upside than even the most promising moonshot technologies.

System-level implications of immediately deployable fuel savings and decarbonisation technologies are myriad for many players in the sector. Airlines can expect immediate improvements to margins of up to 20%, governments and regulators will make more rapid progress on emissions reduction targets, and investors will benefit from reliably improved asset performance and cashflow generation.

Changing the Decarbonisation Narrative

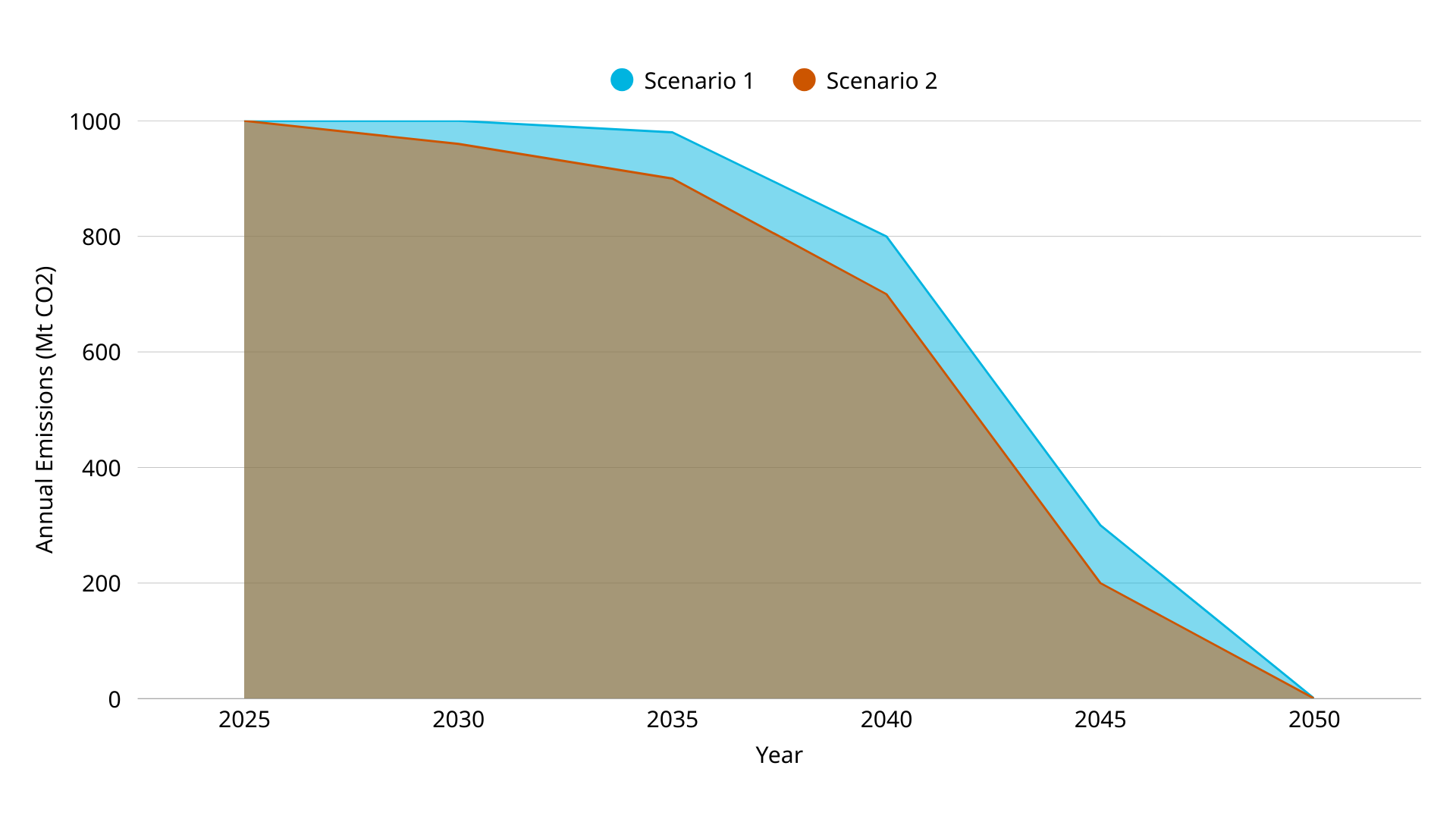

Perhaps of greatest import with respect to industry-wide decarbonisation is the potential for shifting the transition curve downwards far earlier than would otherwise be possible with highly innovative and industry-disrupting big swings. In the illustrative example below, Scenario 1 outlines a possible future in which the first highly impactful interventions in the “Basket of Measures” only come online around 10 years from now. Prior to this, without the rollout of single-digit incremental technologies (sharkskin drag-reduction films, winglets, initial SAF production), emissions are expected to remain relatively unchanged. Scenario 2 outlines the case where these iterative technologies are implemented in the near-term, accumulating fuel savings and emissions reductions in the 10 years preceding the introduction of hydrogen or hybrid-powered flight and wider SAF use. In this scenario, both incremental and more substantive levers are pulled in concert past 2035, creating a decarbonisation ‘stack’ with far greater emissions abatement effect is possible under Scenario 1.

Image: Potential decarbonisation transition curves (illustrative only)

Closing Thoughts

The true impact of deploying incremental efficiency initiatives as laid out in Scenario 2 above is revealed as the difference in area between the two curves, which sums to around 1.6 billion metric tonnes of CO2, or a difference of around 9%. Plainly put, waiting for an aviation decarbonisation panacea stands to leave millions upon millions of tonnes of unabated carbon on the atmospheric table. The aviation industry can unlock the cumulative effect of single-digit efficiency gains right now, with technologies that are certification-ready, retrofittable, and immediately deployable. When applied across thousands of aircraft, a 4% gain becomes one of the most powerful climate and economic levers available to aviation today.